ROAD THOUGH FARNBOROUGH

Farnborough owes much of its early development to being situated on one of the main routes between London and the coast, and thence the continent.

The route originally led to Rye, which was from early times an important fishing and 'cross channel port'. However Rye declined in importance once the harbour silted up and the sea retreated.

The discovery of a Chalybeate Spring in 1606 and the subsequent building of the fashionable new spa town of Tunbridge Wells, created additional trade on the road through Farnborough during the social season from Easter to October. Outside these months the roads were impassable. The rich and famous were attracted to Tunbridge Wells both to partake of the iron and mineral rich waters in the belief that it was a cure for all ills, and also to enjoy the rich social life in the healthy atmosphere of the country, away from the disease and squalor of London. Among those who visited were Queen Henrietta (the mother of Charles ll) in 1630, and later, Charles ll with both his wife, Katherine (the Queen), and his mistress Nell Gwynne. James II and his daughters (who would later become Queen Mary and Queen Anne), Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn. All would no doubt have travelled through Farnborough.

Locks Bottom has undergone several name changes over the years, being 'Brasted Green' for example in 1769, which later became 'Broadstreet Green' (the later name still appearing on some maps as being the area around Tugmutton Common where Starts Hill Road meets Crofton Road).

Green Street Green dates back to at least 1292, under the name 'Grenstretre' (a Roman road overgrown with grass, although nothing is now known of such a road), and therefore the name has no connection with the large open space at the bottom of Farnborough Hill. It too has gone through several derivations of name over the years including 'Grinstead Green', and 'Greenstead Green'. Until 1938 the village, (together with Pratts Bottom, otherwise known as 'Pratts Grove Bottom', and in earlier times as 'Locks Bottom') was part of the parishes of Chelsfield and Farnborough.

Historical Perspective prior to the 18th Century

Prior to the building of the railways in Britain in the 19th century, many journeys were made by water - rivers, canals or coastal shipping - as an alternative to roads. Of course, the ordinary people had no money to spend on fares which, until cheap fares became available on the railways, were beyond their means. Most people were therefore spending their entire life in the town or village in which they were born, never travelling further than they could walk, although this if necessary could be great distances. For the wealthy, they had their own horses and carriages, and more reasons and time to travel.Heavy rain in areas of clay soils turned roads into deep muds and if on a gradient, the road would become a raging torrent sweeping away the mud and causing the road level to sink below the level of the adjoining fields, making them always damp and wet.

The slowly increasing commercial development, together with the military defence of the country, requiring fast communications and rapid troop movements, had created a need. However after the major road building undertaken by the Roman Empire, there had followed centuries of neglect. The Roman roads continued to be used although little or no maintenance was carried out on them, but some stretches survive to form part of today's road network.

Developing Traffic

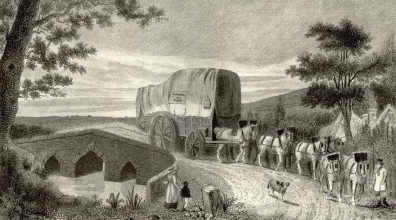

From the early 1500s 'stage wagons', resembling the 'prairie schooners' of the American West of the 1800s, were travelling the roads of Britain. Up to 30 passengers, or a mix of passengers and goods, were carried in these large four wheeled wagons travelling at between 10 and 15 miles a day, drawn by teams of horses or oxen.

|

Different proclamations over the years reduced the laden weight to 30 cwt. in summer, or 20 cwt. in winter, and increased the width of the wheel rims to 16 inches in an effort to reduce the damage to the roads. Fares on stage wagons varied between one halfpenny a mile and 1 shilling a day. On most routes the carriers did not change horses or oxen on the route, but kept the same ones for the entire journey, which obviously increased journey times as the animals became tired. By the 1750s the 'Flying Stage Wagon' had become established on some routes, with the horses being changed along the route, speeding journey times.

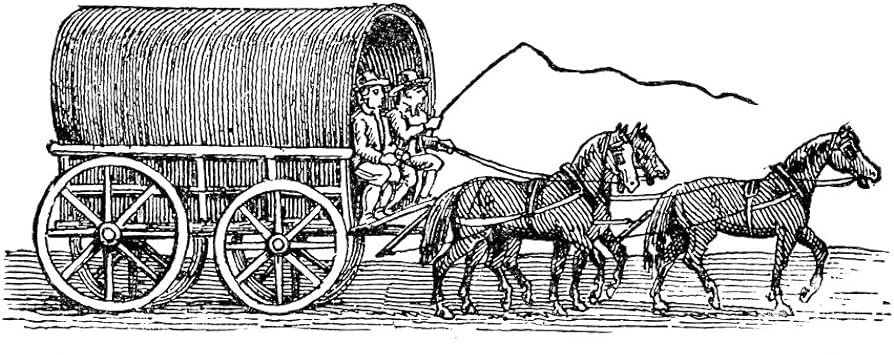

From these stage wagons developed in the 17th century the 'stagecoach' but at first these were often second hand former private carriages previously owned by wealthy families.

Typical of those of the period between about 1730 and 1790 were those with a wickerwork basket attached at the back for luggage and the lowest class of passengers. |

|

An example of this can be seen in a reconstruction in 'A Day at the Wells' exhibition in Tunbridge Wells. Initially, stage coaches only ran during the summer months when the better weather made the roads passable; nevertheless, the number of stage coaches on Britain's roads increased to such an extent that an Act of 1694 required them to be licensed at £8 a year in an effort to bring some control over the numbers.

Travel by stagecoach was harsh, sometimes they would overturn on the rough roads, a situation aggravated if the coach was overloaded as frequently they were, as the driver sought extra fares. Similarly, accidents were caused by axles breaking due to poor construction, overloading, or careless driving. In winter, the coaches were obviously cold, and passengers caught pneumonia, and sometimes simply froze to death, a fate particularly for passengers sitting on the outside of the coach, (a practice peculiar to England, and unknown on the continent).

As stagecoaches started their journeys from the inn courtyards, passengers sitting on the outside had to board in the street as the archways were usually too low for the laden coach to otherwise pass under them. Sitting on the outside, as well as being a cheaper fare, had its attractions in summer time, as the outside passengers were generally more cheerful and talkative, often calling out to passers-by, and schoolboys enjoyed using their pea-shooters. The seat next to the driver was highly sought after, and often by fashionable young men. Stagecoach drivers, as well as holding responsible jobs, were looked up to (in both senses), and highly respected. If life was hard for the passengers, it was worse for the horses, which had a short working-life expectancy of usually only three years.

The weight of the coach rather than the speed imposed the hardest strain on the poor animals as merchandise was charged at higher rates than were passengers, and the number of passengers carried was limited by law. The horses would be whipped and thrashed when exhausted and often died in their harness. That stagecoaches and mail-coaches managed to travel at night, and some travelled only during the night or made early starts at about 3 or 4 am, is amazing. With no street lighting or road signs and even the road poorly defined, the driver was relied upon to know the road, and did not often get lost.

The Roman Road via Holwood.

The Romans, whilst settling in the Orpington and Cray Valley areas, chose to build their road between London and the Sussex coast to the West of Farnborough and Green Street Green, what is now the A233 through Keston and Biggin Hill. The long straight lines so favoured by the Romans were difficult to achieve when crossing the North Downs, although, wherever feasible, the Romans were reluctant to deviate, and would never build bends in their roads; instead adopting angles between straight sections. This road served what is now known to be the location of their long lost market town of Noviomagus, situated near what is now West Wickham parish church off Layhams Road. The road also ran through the Holwood Estate until William Pitt diverted it, via its current twisting course around the edge of the estate, in the 1790s.The course of the Roman road, probably built in the 1st century AD and disused after the Romans left in 410 AD, is still indicated on modern Ordnance Survey maps where it passed through Chart, to the west of Cowden and Hartfield and on to Lewes. One of the few stretches still in use runs from Marlpit Hill through Edenbridge as part of the B2026.

The road had originally run in a more direct route past the original Holwood House (the current building was built on the same site). The 1766 Turnpike Act diverted the road away from the house via what is now the drive of Holwood House, between the two gate lodges. It was later alleged the new alignment was too steep for stagecoaches, which was convenient for William Pitt, as he was now able to purchase yet more land to extend his estate and divert the road, via its current routing, clinging to the hillside.

Route through Farnborough

In the 10th century a track-way was cut through the deep impenetrable Wealden forest, between Sevenoaks and Tonbridge using the direct route via River Hill. Prior to that, the route followed the Roman track-way via Oldbury Hill, Ightham, Fairlawne and Shipbourne to Hadlow and Tonbridge, thereby following the bottom of the Holmesdale and Boume valleys. The river Darent had to be crossed, the only crossing points being a ford at Chipstead, or a bridge at Otford. The climb over the sandstone ridge on which Sevenoaks is situated could be avoided by following a route from Chipstead via Salters Heath, Dibden, Cross Keys, and Hubbards Hill (rather than River Hill).In times of plague many people fled from London into the surrounding countryside, much to the concern of the locals who feared they might catch the fatal disease; and indeed Farnborough did suffer much in this way. King Edward lll spent Christmas 1348 at Otford Manor amid the more healthy country air, travelling via Farnborough.

Mention of Otford reminds us that, prior to King Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries in 1536-1540, regional administration was to a considerable extent in the hands of the church. The Manor of Otford had been granted, by King Offa in 791 AD, to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and therefore the road through Farnborough was an important route for communication between Otford and London. The route ran from Otford via Twitton, Sepham Hilt (the route now blocked by the M25), Otford Lane to Halstead, then Church Road and Stonehouse Lane where it joined the Rye - London road at Pratts Bottom. The early bridge at Otford was built and maintained, as was the road, by the monastery.

Returning to the road from Rye, north of Chipstead the route ran via Chevening up to Knockholt Pound, then down Rushmore Hill to Pratts Bottom, joining the current A21 to Green Street Green. It then ran via Old Hill and Church Road to Farnborough. North of Farnborough the route rejoins the A21 through Locks Bottom to Bromley. The road through Chevening was closed in 1785 when the grounds of Chevening House were extended, leaving today's Chevening Road and Chevening Lane as two truncated remnants either side.

Following the building of the bridge over the Darent at Longford in 1636, the use of the route through Chipstead had declined, the new route joining the earlier route at the foot of Polhill.

At Bromley Common, the 'road' covered a wide expanse of the common. Travellers finding the road waterlogged would pass to one side or the other to find firm ground. Subsequent travellers then had a wide choice of which tracks to follow, although a row of white posts indicated the intended route. North of Bromley the route has always followed approximately the current alignment to Lewisham and Blackheath where it joined up with Kent's other great and original highway, what we now refer to as the A2, based on the Roman built Watling Street from Dover, into London.

By the late '13th century, the London - Rye road through Farnborough was being used for carrying the King's mail to and from the continent. Whilst the sea crossing between Rye - Dieppe was longer than the Dover - Calais crossing, the land route was shorter than the route between London and Dover, and between Calais and Paris. The route up from Rye was also used extensively by traders known as 'ripiers' carrying fish up to the markets in London, the fish being carried by packhorses in trains of c 10 or 12 animals.

The Anglo-French tariff war from 1678 reduced trade with the continent, and what trade there was tended to be via Dover. This, coinciding with the silting up of Rye harbour, ultimately resulted in Hastings, which remained a major fishing port, taking over from Rye in importance from the 1780s.

The first stagecoach through Farnborough appears to have started by about 1680, running two journeys each way every week between London, 'The 3 Tuns' in Gracechurch Street, and the 'Rose & Crown' in the ancient town of Tonbridge. This doesn't appear to have operated for long, but by 1690, a different coach was running the same route, but starting from the White Hart' in Southwark. The number of journeys was the same, although now on different days of the week, with a southbound journey on both Tuesdays and Saturdays, northbound on Mondays and Fridays.

The 'George & Dragon', which features heavily in this story dates back beyond the Elizabethan time. In 1897 John Goodchild Senior possessed, among his collection of antiquities, a 'token' halfpenny issued by William Best of the 'George & Dragon' Farnborough, 'minted' in the reign of Henry VIll". (coinage produced by individuals was not uncommon in past times, in the same manner in which todays traders issue vouchers that can only be 'spent' at their store). Other 'coaching inns' were 'The New Inn' (now 'The Change of Horses: that is thought to date from around 1785, 'The Coach & Horses' which once stood in the High Street near Orchard Road, and the 'British Queen' in Locks Bottom. All three were owned by Fox's Brewery at Green Street Green.

|

|

| George and Dragon | Whyte Lion |

The 'White (Whyte) Lion' in Locks Bottom is another old established Inn, with a date of 1626 claimed. The stables at the rear were unfortunately, demolished by mistake, when the new supermarket, that is now Sainsbury's was built. The Woodman' dates from at least 1823, probably only as an 'ale house' not being named until about 1869, although again, the present building is not the original.

adapted from an original article by Graham Sanders

ROADS AND RAILWAYS

Carrying the Post

King Edward IV in 1481 had set up a postal system to carry messages of state and business across England on the most important routes. Post houses were established about 20 miles apart, with horses available to operate a relay system to speed the messenger. The public were permitted to use this postal system after 1583-4, and after 1644, the postal network was extended to all parts of the Kingdom. The postbags were carried by 'postboys' (the term was used irrespective of age), on horseback or driving postilion a small carriage, who gained a poor reputation for reliability, with slow progress often impeded by intoxication. The postboys, in their distinctive livery of a bright yellow waistcoat, blue jacket, white breeches and a large beaver hat, travelling alone were also vulnerable to robbers. This system however continued long after the widespread introduction of stagecoaches. The livery of the postboys is recalled in the name of the pub 'The Blue Boys' at Matfield.The stagecoach operators at last convinced the Government that they could provide a quicker, more secure, reliable and also cheaper alternative to the postboys. Initially, ordinary stagecoaches were then used to carry the mail, but then Besant and Vidler, based at Millbank, who had the monopoly of hiring the coaches to the mail contractors, introduced a new standard design in about 1785. The new design reduced the number of robberies, as in addition to the armed guards, the mail compartment was lined with thin plates of iron, and the keys not carried on the coach. The guard, with his scarlet coat with gilt arm bands was a figure of authority, employed directly by the Post Office, charged to both protect the mail, and keep an eye on the mailcoach contractor.

These had to keep to strict timetables, and employing the best available carriages (provided by the Postmaster General) and horses, as competition among the rival operators for the contracts was fierce, just as it would be later among the railway companies. The guard would usually be armed with a blunderbuss as well as pistols. The guard would blow his long horn on the approach to a post house as a signal to get fresh horses ready, and also on the approach to tollgates on turnpike roads, and if other traffic or obstructions on the road appeared likely to delay the mail coach. Mail coaches after 1785 were exempt from paying tolls, and tollgate keepers would be in serious trouble if the gate were not thrown open on the approach of the mail coach, and the coach was delayed. The mail coach had precedence over all other traffic on the road. Mail coaches carried a sealed chronometer (an early form of tachograph) to enable the journey times and arrival times to be accurately monitored by the Post Office, in a time when nearly every district had its own time zone. A standard Greenwich Mean Time was not introduced until the 1840s.

Smuggling

Not all the traffic using the road from the coast through Farnborough was legal. With the Kent and Sussex coast the close to France, smuggling goods up to their market in London was rife. Smuggling goods across the English Channel to avoid trade restrictions or import duties has been commonplace for centuries. The smuggling of wool and even live sheep out of England known as 'owling' had by about 1720 been replaced by the importing of tea, spirits, tobacco and luxury items such as lace. The depressed state of the economy in Kent and Sussex at this time meant that farm laborers could earn more for one night's 'work' than a whole week of legitimate hard labour with long hours. Smuggling therefore enjoyed wide popular support from most residents near the coast who saw in this also a way to counter the dominance of the ruling classes which were often corrupt, whilst circumventing unpopular taxation.Despite the popular conception that smuggling gangs were cruel and merciless, this was not always the case. Many were so large that they overwhelmed the government's preventative agents who were employed to stop the smuggling. These agents either chose to 'turn a blind eye' (for which they were often rewarded in gratuities) or were simply powerless to intervene. Many who did try to arrest the smugglers were simply relieved of their weapons, and possibly even tied-up, whilst the smugglers continued with their offloading or transportation, often in broad daylight. The smugglers were secure in the knowledge that they could not be identified and no witnesses would testify against them in court. The situation however became more vicious and ruthless as the Government introduced increasing measures against the smugglers. The penalties increased from imprisonment in 1736 to transportation to the colonies, and after 1746 the death penalty. The 1736 Smuggling Act which enabled a convicted smuggler to be granted a free pardon if they identified and testified against their colleagues, caused smugglers to be suspicious of everyone, and to terrorise anyone who might betray them.

Most of the contraband was destined for the London market, and the finance to purchase the goods abroad in the first place required persons of substance, who often led outwardly law abiding lives of in London. It was also in London thatt most of the customers able to afford the luxuries lived, and once the goods were in London they could easily be mixed in with legitimate goods and their origins become untraceable. The Groombridge Gang, one of the more famous, or infamous, smuggling gangs, were active from 1733. Their favoured route from the beaches in the Hastings area was via Sevenoaks, Knockholt, Rushmore Hill", Green Street Green, Farnborough and Keston Mark. A cache of 2,855 pounds of tea was discovered at about this time in a field near Rushmore Hill. In 1740 an Excise man was captured by smugglers and held at Sprats Bottom near Farnborough. Jacob Pring or Prim of the 'Hawkhurst Gang' (another infamous group) was their agent at the London end of their activities. Living in Beckenham, he would convey the usual consignment of tea onward to the depot in Stockwell, for sale to the London merchants. A customs officer who happened to be watching a cricket match at Bromley Common had to take refuge in the almshouses of Bromley College when he tried to interfere with a transshipment by the 'Hawkhurst Gang'.

During the heyday of smuggling around 1780, armed convoys of a hundred men or more escorting the wagons or packhorse trains of contraband were more regular and frequent than stagecoaches on the main roads in Kent and Sussex. Incidentally, whilst the name 'Bromley Common' is well established, there is now of course no sign of any common land to which it refers. Enclosure Acts of 1764 and 1821 resulted in the commoners losing their use of this land as it was divided up into fields.

The newly formed police force in London, established in 1749 and known as the 'Bow Street Runners', extended their field of operations from the 1780s to main roads within 16 miles of London. There were armed patrols mounted on horseback and two officers of the 1st Division of the Bow Street Horse Patrol were permanently stationed at Bromley Common from 1805. From 13 January 1840 the Metropolitan Police (formed in 1829) further extended their territory into the County of Kent to include Bexleyheath, Sidcup, Bromley and Farnborough areas. This led to the building of Farnborough Police Station at Locks Bottom in 1867 (closed July 1987). It was not until 1st April 1947 that Cudham, Biggin Hill, Chelsfield and Knockholt Police Stations were transferred from the Kent Constabulary to the Metropolitan Police (who promptly closed all of these apart from Knockholt).

The ending of the Napoleonic War signaled the end of wide-scale smuggling until recent times. The defences built against invasion included Martello Towers at regular intervals all along the Kent and Sussex coasts, facing France, including all the likely landing beaches, as welt as the Royal Military Canal, barracks and signal stations along the coast. Both the army and the Royal Navy were now free to turn their increased resources against smugglers. Smuggling thereafter increasingly became a battle of cunning and concealment carried out on a smaller scale and in secret. The tea smuggling trade was stopped by the Government in 1784 using a different method, by reducing the tax from 129% to 12% so the illegal trade was no longer worthwhile.